Iconic programming

Iconic programming is the writing of programs that resemble what they do. It can involve the prominent use of icons, which visually resemble ideas.

Icons and symbols

In semiotics, a distinction is made between icons and symbols. Symbols signify what they reference through convention, while icons signify through resemblance.

This distinction is associated with the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce.

Symbols and icons

Unlike icons, symbols are abstract. They don’t necessarily resemble any concrete thing. Their meaning emerges through convention, as in the everyday rules of a language.

There is nothing about the following set of symbols that immediately suggest

a circle. If we are familiar with some conventions in geometry, English and

JavaScript then we can nonetheless interpret that drawBigCircle(3) will draw

a circle of radius 9.

let drawBigCircle = (r) => {

draw.circle(r**2)

}

Pointers are pointy

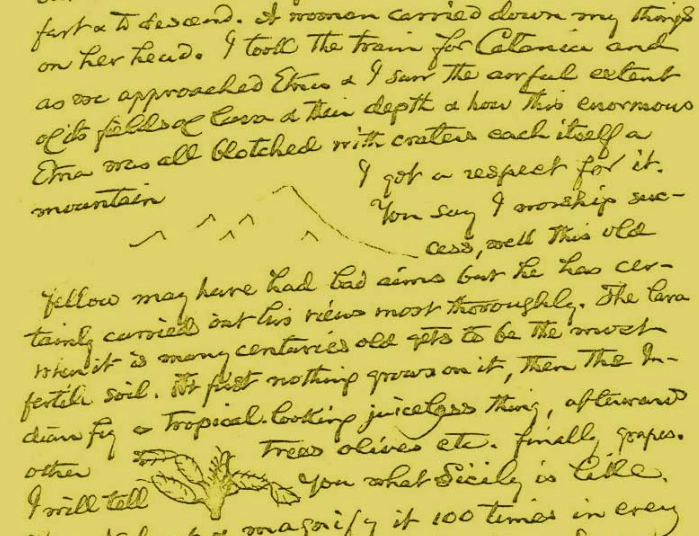

In a letter to his wife from 1870 1, Charles Sanders Peirce used simple illustrations to convey what he encountered in his European travels, including Mount Etna, the craters of which are themselves small mountains.

The ^ in Peirce’s drawings is iconic. It resembles the wide base, steep

sides and narrow peak of a mountain.

Icons can also bear a resemblance to a non-physical concept.

The Odin language uses ^ for its pointers:

pointer_to_int: ^int

In C, * is instead used:

int *pointer_to_int

The Odin documentation states as justification:

Odin borrows the ^ syntax for pointers from the Pascal family, because it is pointy […]

— my italics

The syntax for pointer in Odin and Pascal resembles the concept of what a pointer does: it is pointy because it points 2.

Neither language is fully iconic, as they use combinations of both symbols and icons. The mnemonic and expressive benefits of icons can be leveraged without a wholesale adoption of an iconic language.

Sand falls down

Icons can be used to write programs where the input resembles the output. The following syntax is from SPLAT:

@ => _

_ @

It is a rule: if a particle is above empty space it will fall into that space.

The @ is a particle and the _ is empty space.

In the more accessible SpaceTode — a “spatial programming language” inspired by SPLAT — this rule yields a visual output: particles that fall.

Taken together, the set of characters is itself iconic: the rule resembles the causal event that it generates.

The creators of SPLAT (Dave Ackley) and SpaceTode (Lu Wilson) rightly emphasise the spatial aspect of their work, but I also think resemblance is a notable characteristic.

Comments illuminate

In APL, comments

are prefixed with the ⍝ or “lamp” symbol:

⍝ this is a comment

The intention is that comments illuminate the code. Comments should resemble a (metaphorical) illumination, rather than — for example — a mere recapitulation. This icon is a reminder to the programmer, but not a guarantee of illumination.

Like Odin and Pascal, APL is not strictly iconic, as it contains a mixture of icons and more abstract symbols, often borrowed from mathematics. If you find APL code inscrutable, it’s probably not solely owing to its use of icons.

⍝ for illumination: https://xpqz.github.io/learnapl/aplway.html

⍉2∘⊥⍣¯1⍳2*3

Not just boxes

Visual programming is often contrasted with conventional, text-based programming. Visual programs typically rely on graphical elements, like boxes, which can be dragged and connected. These interfaces can be more convenient for specific users or for particular use-cases.

Icons resemble what they represent, while a box is symbolic, an abstraction.

Programming with icons does not require a graphical user interface.

I can type or write ^ ^ ^ to represent a mountain range without a GUI.

Here are some other icons with possible spatial interpretations:

^pointer!filter()container(())nested containeroloop#grid/gradient@atom

The concept of “resemblance” is not necessarily spatial:

The stimulatory effects of coffee resemble that of tea

Conceptually, all games share a family resemblance with each other

Why icons?

I might like to program with icons because they have an immediate conceptual similarity to what I am trying to make, and the immediate mechanical simplicity of that which can be typed.

This does not have to result in a needless multiplication of symbols, but there is a non-trivial challenge in selecting a finite set of icons that can capture highly generalisable ideas. For example, ideas like parthood, connection and enclosure are highly general, span numerous contexts and can be combined in many ways.

A language does not need to be fully iconic, but can leverage icons to make

abstract concepts more concrete. An excellent example here is the use of the

pointy ^ for pointers in Odin and Pascal.

Pipes

Just as pointers can be pointy, pipes can be…pipey.

In Unix, the

|or “pipe” is used to compose a pipeline of commands.cat log.txt | grep "error" | sort | uniqThe

|seems to resemble a pipe, although I could not find any evidence of this being a reason for its original selection.

There is something powerful about the idea of “resemblance”. How can programs be made to look and feel more like what they do? What important non-visual resemblances exist and how can they be represented?

References

- Future of Coding episode 72: podcast about Pygmalion, a prototype for a programming environment that uses “icons”, although the original author does not use the term in the strict, semiotic sense.

- Ivan Reese’s visual programming Codex: organised collection of visual programming tools, concepts and discussions.

- Dave Ackley’s SPLAT: Spatial Programming Language, ASCII Text, which I think has some iconic aspects.

- Lu Wilson’s SpaceTode: a spatial programming language, which I think has some iconic aspects.

Nubiola, J., & Barrena, S. (2012). Drawings, Diagrams and Reasonableness in Charles S. Peirce’s Letters during his First Visit to Europe (1870-71). In Das bildnerische Denken: Charles S. Peirce. Retrieved draft version from https://www.unav.es/gep/Nubiola&BarrenaDrawings.pdf on Fri Apr 25, 2025

The meaning of an icon depends on the context of its use. We can use ^ to

represent a pointer to a memory location or to represent a mountain.